Oxford researchers have predicted the impact of rising temperatures on climate adaptation requirements for cooling on a country-by-country basis if climate targets are missed

Switzerland, the UK and Norway will see the world’s most dramatic relative increase in days that require cooling interventions – such as window shutters, ventilation, fans, or air conditioning – if the world overshoots 1.5oC of warming, according to new University of Oxford research.

- Amongst countries with more than 5 million inhabitants, Switzerland, UK and Norway will see the world’s most dramatic relative increase in uncomfortably hot days, but are under prepared

- When considering smaller nations, Ireland will be the most affected

- Central Africa will see the most extreme temperatures overall

- Striving to remain below 1.5oC warming is essential to mitigating these impacts

- The research aims to inform COP28 where the UN and host nation UAE hope to develop a “Global Cooling Pledge.”

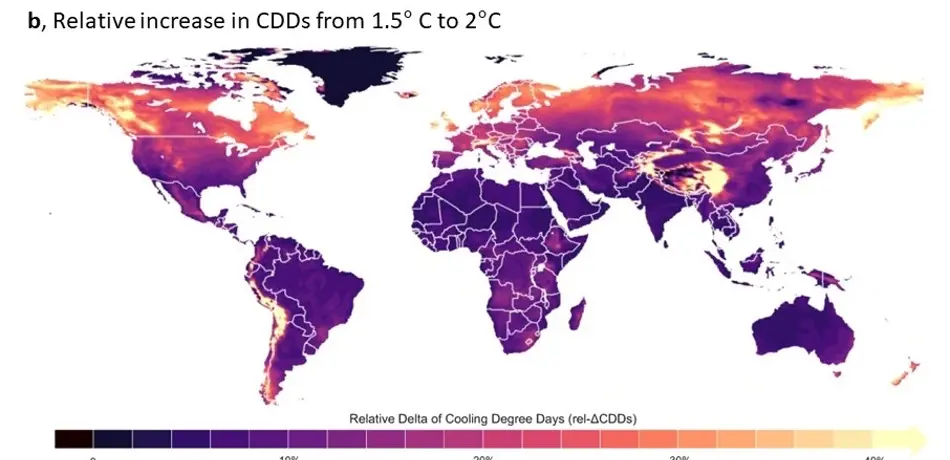

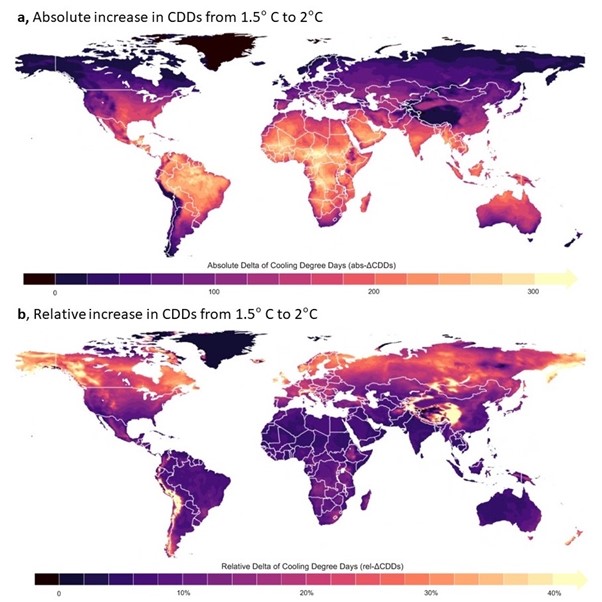

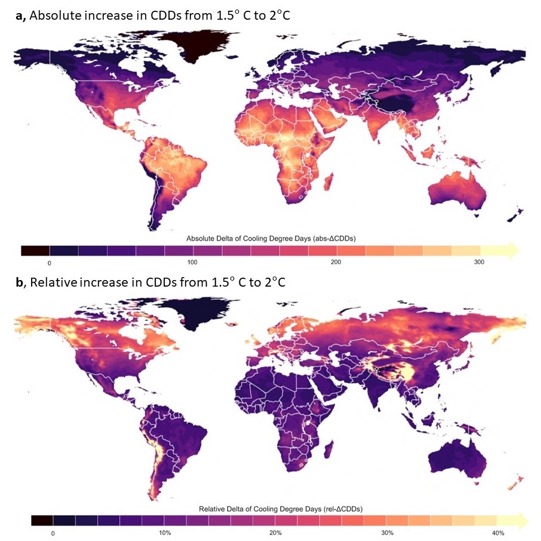

Switzerland and the UK will see a 30% increase in days with uncomfortably hot temperatures if the world misses the 1.5oC target and heats to 2oC, while Norway will see an increase of 28%. The researchers stress that this is a conservative estimate and does not consider extreme events like heatwaves, which would come on top of this average increase.

Switzerland and the UK will see a 30% increase in days with uncomfortably hot temperatures if the world misses the 1.5oC target

8 of the 10 countries with the greatest relative increase in uncomfortably hot days are expected to be in Northern Europe, with Canada and New Zealand completing the list. Buildings in northern Europe are usually designed to keep heat inside, so can be at risk of overheating in hot weather. Therefore, even with a moderate increase in temperatures the heat rises will be very impactful and will need large deployment of cooling adaptation measures. The researchers believe these countries are dangerously underprepared for this change.

Co-lead author Dr Jesus Lizana, Postdoctoral researcher and Marie Curie Fellow at the Department’s Energy and Power Group, explains, “If we adapt the built environment in which we live, we won’t need to increase air conditioning. But right now, in countries like the UK, our buildings act like greenhouses - no external protection from the sun in buildings, windows locked, no natural ventilation and no ceiling fans. Our buildings are exclusively prepared for the cold seasons.”

Co-lead author Dr Nicole Miranda, senior researcher in the Energy and Power Group, adds, “Northern European countries will require large-scale adaptation to heat resilience quicker than other countries. The UK saw massive amounts of disruption in the record-breaking heatwaves of 2022. Extreme heat can lead to dehydration, heat exhaustion, and even death, especially in vulnerable populations. It’s a health and economic imperative that we prepare for more hot days.”

Northern European countries will require large-scale adaptation to heat resilience quicker than other countries

The top ten countries that will experience the highest needs for cooling overall in a 2.0oC scenario are all in Africa, with central Africa most affected.

For their analysis, the authors used the concept of “cooling degree days,” a method widely employed in research and weather forecasting to ascertain whether cooling would be needed on a particular day to keep populations comfortable. They modelled the world in 60km grids every six hours to produce the temperature averages in the study, a process that makes the results some of the most reliable globally. The models were run by Professor David Wallom and Dr Sarah Sparrow using the citizen science project climateprediction.net (CPDN), which uses tens of thousands of volunteers' computers.

Co-author Dr Radhika Khosla, Associate Professor at the Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment and leader of the Oxford Martin Programme on the Future of Cooling, says, “Without adequate interventions to promote sustainable cooling we are likely to see a sharp increase in the use of energy guzzling systems like air conditioning, which could further increase emissions and lock us into a vicious cycle of burning fossil fuels to make us feel cooler while making the world outside hotter.”

“Cooling demand can no longer be a blind spot in sustainability debates,” concludes Dr Khosla. “By 2050 the energy demand for cooling could be equal to all the electricity generated in 2016 by the US, EU and Japan combined. We have to focus now on ways to keep people cool in a sustainable way.”

‘Cooling Degree Days,’ or CDDs are used in research and weather forecasting to help quantify the heat exposure or need for cooling. They are worked out by calculating the difference between the average daily temperature and a baseline temperature, which is normally 18oC.

Unlocking the Mysteries of the Universe with Radio Telescopes

Scientific Computing